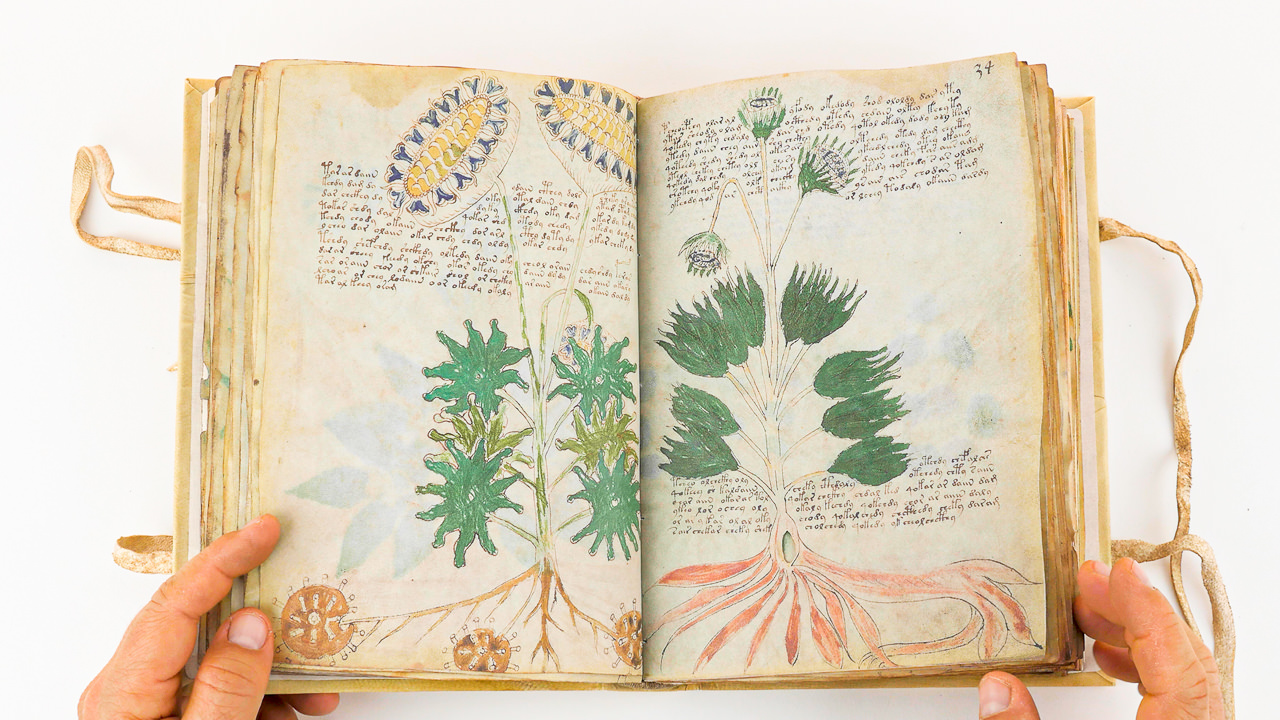

The publication of Yale University Press’s The Voynich Manuscript - the first-ever authorized edition available to the public - allows a new generation of acolytes to gain access to this most mysterious of bequests. Despite its virtually never leaving the Beinecke Library, curator Raymond Clemens believes it to be “one of the most viewed and discussed artifacts from the medieval period, perhaps second only to the shroud of Turin.” Historian Deborah Harkness describes the binding as “the Renaissance equivalent of a paperback: inexpensive, limp vellum.” Suffice it to say, the book’s lasting fascination stems from its baffling contents, rather than any outward aesthetic grandeur. The manuscript itself is small, its pages browned and gnarled.

In reality, Beinecke MS 408 (the book’s official name in Yale’s Rare Book & Manuscript Library) is nothing much to look at.

With this rich, Eco-esque backstory, replete with the romance of esoteric codes and heated interpretive grappling, one would be forgiven for imagining the Voynich to be a gorgeous material object, gold-clasped, bound in soft leather, its pages edged in dye. The mystery that had survived for five centuries would live on for another. Newbold’s very public failure appeared to dissuade would-be cryptographers from entering the arena for some time. He wrote of the Voynich author, “I could not believe that a man with intelligence enough to construct so complicated a cipher would construct one that could not be trusted to convey his messages inevitably and unmistakably.” With additional debunking in popular and academic journals, Manly was able to convince Newbold’s supporters that his “unsystematic re-arrangement of letters” could not, in fact, be the long-awaited key.

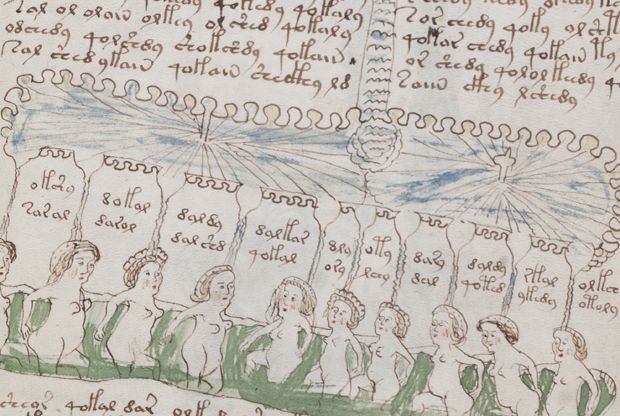

Voynich manuscript for sale code#

It seemed the Voynich had at last been cracked.īut John Matthews Manly, who had worked as a code breaker during World War I, was not so easily convinced. Newbold produced compelling evidence, including descriptions of obscure historical events he supposedly found within the manuscript. Newbold believed the enigmatic text had been written by the 13th-century polymath and radical Franciscan Roger Bacon, whose capacious intellect and controversial scientific observations - eminently cipher-worthy - made him a seemingly ideal candidate for authorship. Manly’s article was written in response to the news that the book’s as-yet-unsolved cipher had been decoded by William Romaine Newbold, a medievalist at the University of Pennsylvania. Voynich.” The volume, which came to be known as the Voynich Manuscript, was an early 15th-century codex written in an entirely invented script, its pages adorned by illustrations of plants, stars, and astrological formations with no known analogues in the observable world. “Few literary discoveries in our time,” wrote Manly, “have excited a keener or more widely spread popular interest than those connected with the mysterious volume brought to light nine years ago by Mr. Although they had once been close friends, Manly felt a moral imperative to publicly denounce Newbold’s work in the “interests of scientific truth.” “In my opinion,” he wrote, “the Newbold claims are entirely baseless and should be definitely and absolutely rejected.THE JULY 1921 ISSUE of Harper’s featured an article provocatively titled “The Most Mysterious Manuscript in the World,” written by one John Matthews Manly, a professor of English at the University of Chicago. Newbold’s solution was debunked in 1931 by University of Chicago classicist John Matthews Manly in a journal of medieval studies called Speculum, leaving Newbold posthumously disgraced. In June 1921, the monthly magazine Hearst’s International announced that University of Pennsylvania Professor William Newbold had “come upon the key to the secret cipher of the Manuscript … and the truth of six hundred years ago is coming out!” Newbold surmised that 13th-century English scientist Roger Bacon had written the manuscript with the aid of a microscope and a telescope, centuries before the invention of either instrument. For centuries, the Voynich Manuscript has resisted interpretation, which hasn’t stopped a host of would-be readers from claiming they’ve solved it.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)